In this article, I aim to shed light on the inner workings of GitHub Copilot, a tool that’s revolutionizing how developers write code. Whether you’re a seasoned developer or just curious about AI in coding, this exploration will offer insights into the algorithms and processes that power Copilot, helping you understand its functionality better.

Overview of GitHub Copilot’s Architecture.

GitHub Copilot integrates with your IDE (like VS Code) to provide code completions and generate tests. Here’s a simplified view of the components involved:

- IDE (e.g., VS Code)

- GitHub Proxy

- OpenAI

Here’s a basic workflow:

- You write code in your IDE.

- Your IDE sends a request to the GitHub Proxy.

- The GitHub Proxy forwards the request to OpenAI.

- OpenAI processes the request and sends back a response.

While the specifics of GitHub Proxy are proprietary, we can focus on how VSCode interacts with it.

Setting Up the MITM Proxy

To gain deeper insights, we’ll use a MITM (man-in-the-middle) proxy to intercept and analyze the requests and responses between VSCode and GitHub Copilot.

What is a MITM Proxy?

A MITM proxy not only forwards and encrypts traffic but can also intercept and decrypt it, allowing us to inspect the data in detail. This process involves:

- Installing a MITM Proxy: I use Docker for this purpose. Numerous online tutorials can guide you through the installation process.

After installation, we see the following picture:

2. Configuring VSCode: In VSCode, navigate to File -> Preferences -> Settings. Search for proxy and set the address to http://127.0.0.1:8080 (or your proxy’s address). Ensure the proxy is configured for the user rather than the workspace.

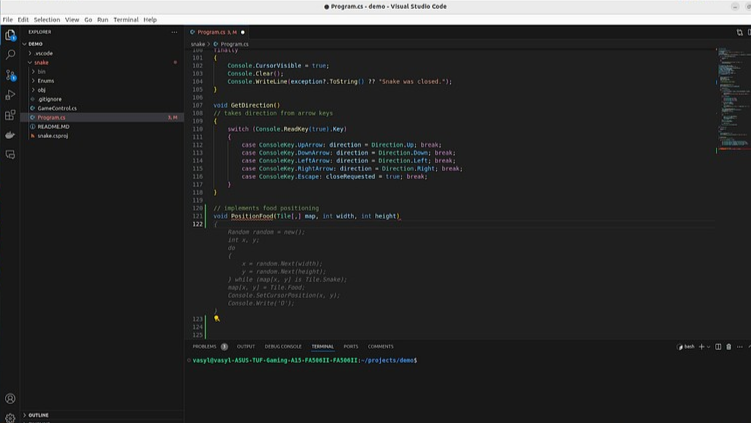

Demonstration: Writing a Simple Game

Let’s write a simple game — Snake — using GitHub Copilot.

I have prepared a basic version of the game that you can find on GitHub. For demonstration purposes, we’ll focus on the PositionFood method, which is responsible for placing food on the game map.

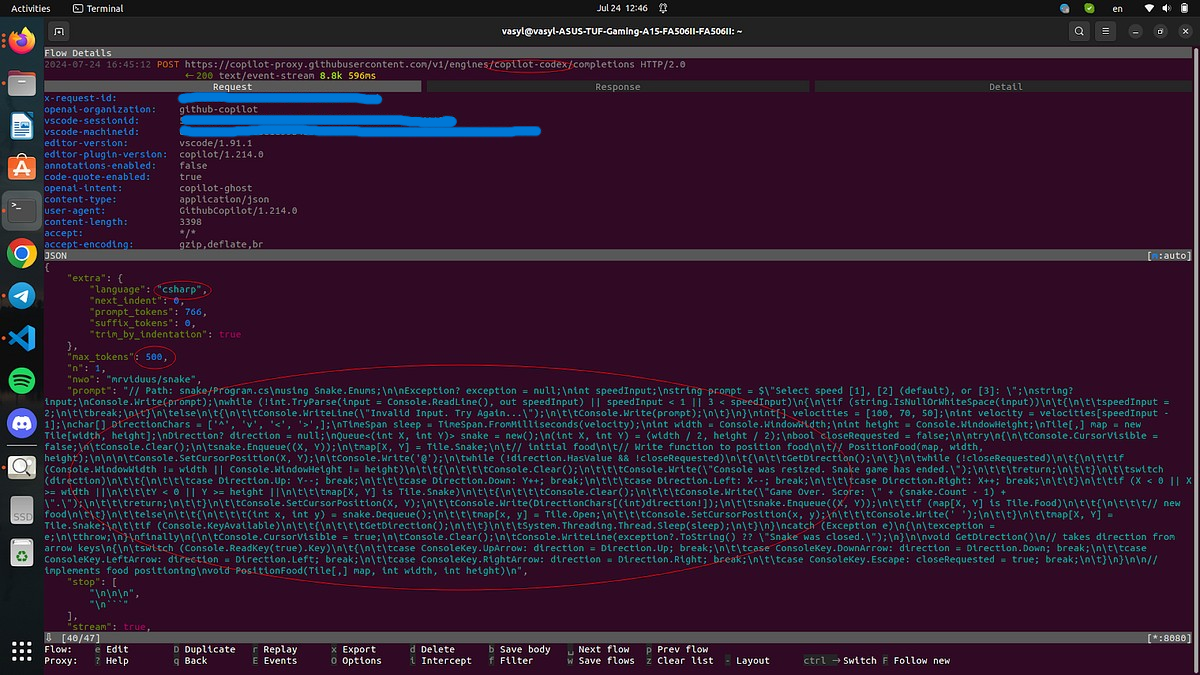

When we request Copilot’s assistance to generate this method, the IDE sends a POST request to:

We go inside it and see the following picture:

Understanding Requests and Responses

Request Details and Prompt

Examining the POST request, you’ll notice:

- URL Components: The URL includes copilot-codex, a nod to Codex, the AI model that preceded ChatGPT. This reference is a link to Copilot’s legacy. (Let’s delve a bit into the history. Before OpenAI created ChatGPT, they worked on an AI specifically for writing code, and its name was Codex. Currently, Codex is considered legacy. This url as a kind of reference to the past.)

- Tokens: Tokens are a unit of currency in API interactions. They help determine the extent of the request and response.

The IDE constructs a detailed prompt before sending it to GitHub. This prompt includes:

- Code Written So Far: It includes the code you have already written.

- Suffix Field: This part of the prompt includes the code immediately following your cursor.

Fields such as:

- Temperature

- top_p

These two fields determine how creative the response should be. If you want to study these parameters in more detail, they are described in the OpenAI documentation. It’s a separate and interesting topic that I won’t cover here.

Response

Surprisingly, we do not receive JSON. But what is it? The fact is that GitHub Copilot uses the SSE protocol for interaction.

Server-Sent Events (SSE)

Copilot uses the SSE protocol for real-time updates:

- What is SSE?: SSE allows servers to push real-time updates to clients over a single, long-lived HTTP connection. Unlike WebSockets, SSE is unidirectional — data flows from server to client only. This makes it ideal for real-time updates like code completions.

To sum up this part. Our IDE generates a prompt, sends it somewhere in Azure where OpenAI is hosted, then OpenAI generates a response and sends it back to the client using the SSE protocol. This all happens so quickly that we don’t even notice it in our IDE.

Advanced Features

Working with Multiple Tabs

When working with multiple open tabs, Copilot constructs its prompt based on the content of these tabs. It includes comments from other files to provide context, although this behavior is constrained by token limits.

To show the next part, I will move the GetDirection and PositionFood methods to a separate class: GameControl. In my code, I intentionally left a few spots that are not fully completed. For the demonstration of the next scenario, I will open two tabs in VS Code, place the cursor where I need to add a few lines, and Copilot will suggest how to complete them. So, let’s take a look at the result.

I perform the same file-saving operation and am interested in the following result:

In this part of the request, we see that the prompt is constructed based on the number of open tabs, and what Copilot does is add all the text as a comment at the beginning of the prompt. From Copilot’s perspective, we are working with only one file, but what it actually does is take a bit of context from the open tabs and add it at the beginning of the file as a code comment.

The important part of all this is that we have no control over this behavior. It’s also worth noting that the file size matters; for example, if you open a large enough file or if there is a lot of code in another tab, Copilot won’t add anything. This, again, is due to token limits and the computational power in Azure, which costs money. So, in conclusion, for complex enterprise systems, this feature doesn’t work well.

Tip: There’s a small trick I sometimes use in my projects: if the number of lines is large and I need to give Copilot a bit more context, I manually copy the necessary part of the code and paste it as a comment, essentially replicating what Copilot does. I understand this isn’t an ideal solution, but I hope it will be improved in the future.

Query

The next small part is the query. This is also the part of the request that is described in the documentation and is a parameter that can be adjusted.

Here’s how it looks.

I would also like to demonstrate how the suffix works visually.

I consider this an important part because in previous versions, this feature did not exist in Copilot, but it is now implemented and works quite well.

Exploring Copilot’s Chat Feature

And probably one of Copilot’s main features is its chat. Let’s also take a look at what it offers. I will ask Copilot to complete the same method, PositionFood.

I will once again remove the unnecessary and leave only the essential.

The differences from the previous version are obvious.

Here, we see prompt engineering.

In the main part, we see Microsoft’s policies that must be followed, and it also specifies the format in which the response should be provided.

Additionally, a specific model is mentioned that we can use, which suggests that perhaps we use something different in regular usage, but this is just my speculation.

Test Generation

Actually, this part doesn’t differ much from the previous version.

But when we send a message to the chat, several requests are sent at that moment:

We have already considered one of them above, there is no point in dwelling on it, let’s consider the next one.

Here, as we can see, the Copilot sends a request in addition, in which it asks to generate the next hypothetical request from the user.

Here we see that a different model is used. But overall it is very interesting how it is implemented, an additional request is sent which, based on the previous answer, generates a hypothetical request from the user, which is quite an interesting find.

Conclusion

GitHub Copilot leverages advanced AI and real-time communication protocols to enhance coding productivity. Understanding the underlying processes and interactions between your IDE, GitHub Proxy, and OpenAI can help you better utilize Copilot’s capabilities. As AI tools like Copilot evolve, they promise to further transform the software development landscape, making it essential for developers to stay informed and adapt to these changes.

Leave a comment